Москва́ – Moscow

One night. The only rare interruption is given by train wheels lulling me across the 750 kilometers that took me from Saint Petersburg to Moscow. A few grumbled Russian words get spoken in the darkness. It’s going to be Moscow soon.

Twice, here, in 2004 and in 2010. Years dig you, and blunting your heart and shortening your life, they can change immensely how you perceive the same human and geographical place. I won’t follow any logical order to describe this gigantic city. I will be a mad magician, taking out faces, smells, noises and jolts from the blurring hat of memory.

Lyrics from an Italian song by Francesco Guccini keep spinning in my mind:

“Thousands of empty eyes, and thin hands clinging on wires, and years of agony, where nothing is your everything”.

When you see those hollow little faces, in the tube stations of Moscow, you come to realize how our boredom becomes similar to a burp. Sometimes, they hide there, in holes, like maddened rabbits, and you can forget that thousands of children are there like some dirt which is taken away by the wind. They suck their lives from plastic bags containing glue, a drug that can eradicate hunger and thirst and overshadow their chance to childhood.

In those stations, as charming as dancing rooms, another frightening memory comes back to haunt me: the bomb attack at the Riskaia station. The day before Breslan, my parents rang me, and shouted over the phone that I had to get the hell out of the tube, because a terrorist attack had taken place, and I had to live. I immediately checked the tube map: I was 6 stops before Riskaia. 6 stops made of breaths, laughter, made of life that keeps going on for me. A woman kamikaze killed ten people on that day, on the 31st of August 2004. I passed by outside that station two days afterward, and one object sticks out of my memory: a shoe splashed with blood. Anger rose, and all I wanted to do was screaming at them “You are all assholes! You cleaned almost everything around here, and you left this shoe. Why didn’t you give it back to their loved ones? Maybe they are still looking for it around!”. When you lose someone dear, you look for them in their everyday objects, in their clothes. The day after means Beslan. History becomes a gruesome trail, dark and rotten.

Then a rabbi. My godless steps, uncertain. His synagogue lit up for me. In my head, this rabbi’s voice, telling me how welcome everyone was in his place. His soft smile, his relaxed way of delivering in English typical of those people whose god was benevolent but at times absent minded. People like him can guide this world towards a better and more tolerant future. We share bread and cheese on the steps of his faith. I looked at the Kremlin, pulsating symbol of the political Russian power, but once paradoxical epicenter of the orthodox church. From those 2,5 kilometers of walls, dictators, tzars, and presidents have directed the best and the worst of this unforgettable country, under the protection of the ruby star shining on the Red Square, or Красная площадь. Once this place used to be known as Požar, as all buildings around it used to be burnt down by fires. They then started to call it Красная, which in Russian means both red and beautiful.

And beautiful it is indeed. Your legs shake a bit, because History walked here. Saint Basil Cathedral stands in front of you, and you expect to see Ivan the Terrible to come back out of nowhere to celebrate some new Kazan conquests. Then, you can see Lenin’s pyramidal mausoleum. His mummy must have felt pretty lonely, as over the decades other important puzzle pieces, such as Stalin and Jurij Gagarin, were placed to rest there. Picture this: the three of them, small glasses of vodka, after years of stiff motionless days. All they dreamt was to stretch their backs a bit. They look at each other and the question pops up, quite naturally: “Where’s Chruščёv? I can’t believe he’s still playing with those Cuban missiles!”. In that moment, a woman appears on the stage of our fantasy, heavily eye-browed, with revolutionary manners. She seems to know quite a lot about military toys too. She grunts “Vladimir, how many times do I have to remind you? Chruščёv is not late. He is at Novodevičij. Gogol, Checkov, Majakovsky, Einstein and Prokofiev tell me that he behaves. He doesn’t play with missiles and popes anymore”. “Thank you, Nadežda, you are my never ending blessing. It’s so fortunate that we got a chance to spend the rest of eternity together. Where would this world go without women?”. Shush, now. Silence. Gloomy guardians remind the spirits to behave.

On the other side of the square a different kind of show awaits the traveler. GUM stores, 80,000 square meters of excellent boutiques, with a glass roof, where old and new Russian elite gather to spend some rubles. No sign of those empty eyes here. It’s funny if you think that these walls were where Russians used to get bread, milk, and now have become The Place where “you can make your shopping” as the official website explains in shaky English

http://www.gum.ru/en/.

My favourite section of Moscow was Kitay Gorod, east to the Red Square. Kitay Gorod is one of the oldest districts of the Russian capital, and it was founded in the 13th century as a trading market place. Square walls, six meters by six, circumscribe this jewel within a bigger jewel. My memory of these streets brings back the image of some architecture students, sitting between Synod publishing house, where the first Russian book was ever printed in 1536, and the Monastery of the Sign on Varvarka street. Its golden domes, the sun setting. These students observe each details with the greatest attention, and try their best to re-create an impossibly beautiful reality onto their sheets of paper. What are they dreaming about? Do they want to become the next Renzo Piano? Or do they dream about an untimely wedding, a car, fresh bread and milk in the morning, because life is simple, and precious because of this simplicity.

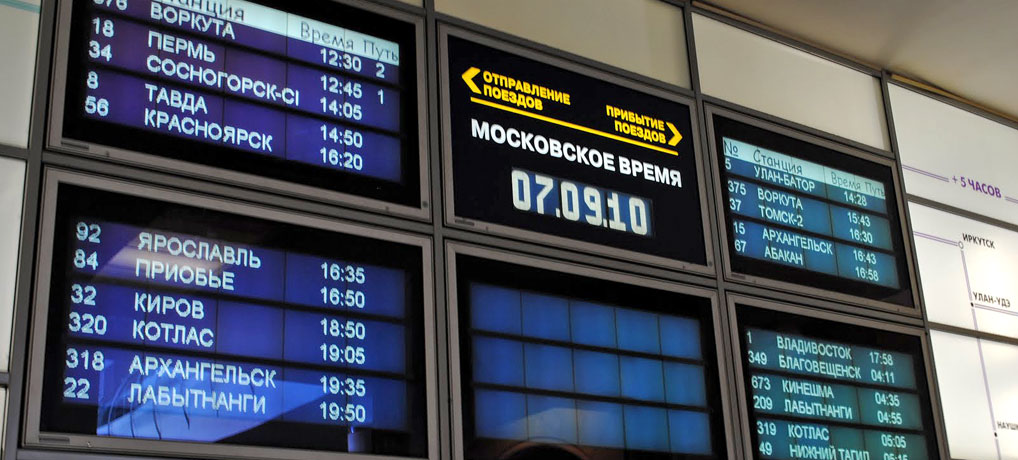

My permanence in Moscow is nearly over. Next stop will be Perm. I will be leaving from Yaroslav Vokzal, one of the most important stations for travellers going toward the end of our reassuring Europe. One last piece of memory remains, before I get on the train for one of the longest routes of my Transmongolian trip: Katarina’s doubtful smile and our consequent conversation in extremely unstable English and hilarious Russian. She looks at my absurd backpack, and she doesn’t seem to be able to take her eyes off my short hair. She’s 22 years old, 2 children and her husband seems to love her very much. Her first question is where my husband is. When I tell her that I have no husband and probably will never have one, she is shocked but recovers soon to inform me that it doesn’t really matter, because I am way too old to find a partner. She then proceeds to list the positive aspects of having a man in your life: men can lift your suitcases, or they can defend you in case something goes wrong on the train, for instance. They can also fix your car if it breaks down in the middle of the Siberian steppe. They can remind you how pretty you look.

Is Katarina right, I wonder?

And I thought this was way the best part of my life, 30 years of age, as free as a river. She then wants to know why I keep my hair so short. Was I recently sick, she wonders? I start laughing out loud, and I let her know that for most of my life my hair has been pretty damn short. Her husband would never look at a gal like me, who looks a bit like a boy. She ventures to say that maybe this is why I don’t have a husband? By the way I am reporting our conversation, it feels like Katarina was a terrible person. Quite the contrary: Katarina was one of the best trips I have had in my life. Travelling means walking on bridges that take you where values and beauty canons vary immensely.

T.S.Eliot once wrote that

“We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time”.

We travel through the ideas of those we meet on trains, on airplanes, at the small restaurants on the other side of the planet. Our conversations are immense trips, which will lead us to become wider, better people. Tolerance gets built in this way. Peace originates from the way those other eyes perceive the same starting point.