Stockholm Underground

It is freezing cold outside, and the arctic night has already settled over the almost deserted city on this December afternoon in 2022. I descend into the belly of the earth. Thirty or more metres below street level, and I find myself in a somewhat psychedelic realm. Checkerboard floors, classical statues, and spiralling pillars. I am in Kungsträdgärden, one of Stockholm’s underground stations. Down here, hundreds of people come and go, students, travellers, and children stuffed inside colourful thermal suits.

And this is precisely why I have always liked the subways of the world’s cities: life pulsates along these 110 kilometres of tracks that connect the entire Swedish capital, but at the bottom, these tracks are also an idea of unity, an idea of the greatness of Humanity that not only physically enjoys art but becomes part of it.

The Stockholm Metro was officially born in 1933, as a ‘pre-metro’. Kungsträdgärden is not the oldest stop in what is described as the world’s longest art gallery: the record belongs to the nearby T-Centralen, whose cavernous interior is covered in bright blue leaves and masonry shadows in 1957. Over the decades, it is estimated that more than 150 artists have participated in this immense shared creative experiment. From a certain point of view, it can also be said that it is a very democratic way of exhibiting art: all you have to do is buy a ticket. Perhaps one can also go so far as to say that the Stockholm Metro system is a giant historical document: depending on where you stop, you can enjoy post-modern art (related to the 1980s), or political art, typical of the 1960s.

However, not everything has always gone smoothly, as is often the case in the construction of large urban works: in the early 1970s when work began on Kungsträdgärden, residents took to the streets in protest, concerned about the destruction of the centuries-old trees in the historic park above. Their complaints became known as the Elm Conflict, but are now a distant memory since the station has become a celebrated cultural destination. Strange to call a station or an entire transit network that, isn’t it? History, however, often overturns the world’s needs and priorities.

The Stockholm metro network comprises 100 stations, and 94 of them have been transformed into art installations. Some of them have even been called ‘cave stations’: these caves carved into the rock are very fascinating and do not remind me of anything negative (like hell) as I go up and down to see at least the most spectacular ones. One of the most impressive to me is Stadion: in 1973, Enno Hallek and Ake Pallarp illuminated this stop with a coat of blue paint on the ceiling and superimposed a rainbow that spins all around. As is often the case, this creation then brought about a socio-cultural change: since then, Stockholm Pride has started to focus on the Östermalm district. The rainbow not only brings cheer to those passing through but is also culturally appropriate. As I pass through this station, I am strangely reminded of fishing boats going out to sea, on a calm and geographically unspecified sea. I am also reminded of the Lascaux paintings: the walls speak to us and have represented Humanity from far and wide.

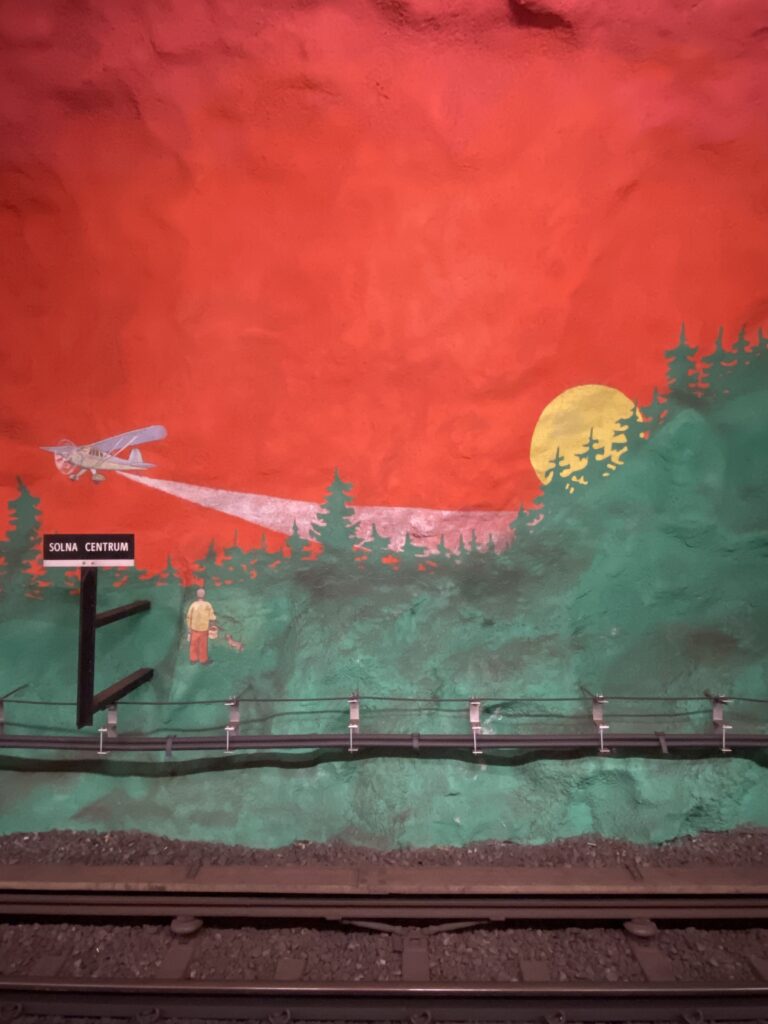

A completely different sky is the one I encounter at the Solna Centrum stop: here the walls and ceiling are bright red, red like passion, vitality, and tomatoes. In the midst of this Dantean fire, I experience two quite contrasting feelings: the first is precisely life, normality, and the greatness of our existence, which is represented by a farmer sowing a field, houses, trees, and a moose. The second is probably influenced by my personal interests: I feel I am in a dystopian novel. The earth is burning around me, but I sit here quietly waiting for the metro.

The Odenplan Station is dotted with hundreds of metres of jagged LED lighting on the ceiling. Maybe it’s a professional distortion, but I immediately see something medical about it, and for once I’m right: it’s a representation of the heartbeat of the son – not yet born at the time – of David Svensonn, creator of the work entitled Life Line.

At City Station, things change again: here I find myself in an endless kaleidoscope, light as a feather. A mirror at the beginning of the escalators projects light onto a series of suspended prisms that in turn bounce coloured patterns off the walls. At City Station, one writes and paints with light in an immense commuter cathedral. My head doesn’t develop post-apocalyptic theories here: I feel like I’m standing on the threshold of a ceremonial hall, in the presence of the Force (to quote Star Wars, so incidentally), inside a sacred dome pining for some kind of Heaven, where everyone coming and going shares a very defined moment of beauty.

The world’s longest art gallery will become even longer in the next ten years: there will be an extension of the blue line and a new yellow line. New works will appear in dozens of stations, as many artists have already been appointed to secure their creations. I will have to make that effort and come back to see what other magical worlds will appear down here, in the belly of the Swedish earth.

[If you want to read another Swedish story from many years ago, click here].

Ok, will visit this architectural wonder in September for sure now 🙂

Great how you always seem to find the most special places.

Thanks a million, Anna. I really hope you will like this wonderful art gallery! Enjoy Stockholm!