The Abbey of Saint-Roman

I’ve grown a new nose

It’s Friday, late afternoon.

The working week ended a little while ago and, turning off my computer and my work mobile, I can finally welcome the weekend. Since I’ve been in the South of France, I realise that every day brings a discovery, an expectation, a burst of pure joy because everything, even what might normally seem a simple or obvious action, has a new smell here and is an opportunity to get involved and rediscover the real pleasure of travelling.

I have no time constraints, no one is waiting for me anywhere, and after all only the people who are really important to me, both personally and professionally, know where I am. This sense of total detachment from everyday life makes me incredibly light after two years in which everyone knew, incessantly, where everyone else was.

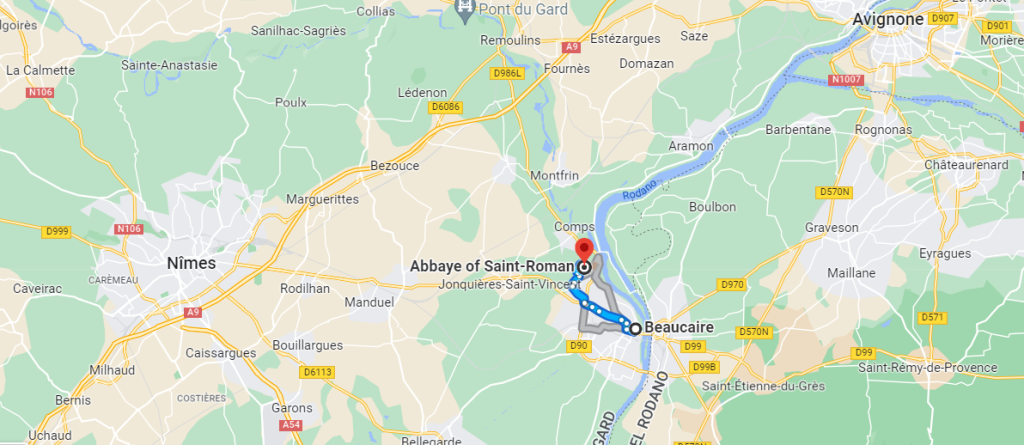

It’s Friday, late afternoon, as I was saying. I get into my car and in less than 20 minutes from Beaucaire, I arrive at the car park of the Abbey of Saint-Roman, which, as often happens in France, is well signposted even many kilometres before my destination. There are no other cars in the clearing, just two huge motorbikes in front of which two friends (I imagine they are friends) are chatting. One of them is showing the other some photos from his mobile phone. They both have the classic biker look: long grey hair tied just below the nape of the neck, both wearing t-shirts of world-famous rock bands, and a black leather waistcoat on top. Big polite smiles when they see me, Bonsoir mademoiselle, and I would like to ask how old do you think I am when you call me mademoiselle. I greet them, mumbling something grammatically questionable, and take the small path from the car park to the entrance of the abbey.

All around me is an authentic olfactory landscape: the Mediterranean scrub becomes an orchestra through which thyme, holm oaks, Aleppo pines, broom shrubs and cistus, rosemary and wildflowers blend to create a symphony that runs and runs and reaches the sea, which is not so far from here. These are aromas I know very well because after all, I am Mediterranean as well as European.

They are essences that in my life have often been treasured in the various kitchens of my part of the world, but also in medicine, and in the composition of perfumes. And yet, on this late Friday afternoon, with these mild temperatures for mid-October, it seems to me that these scents are stronger, sharper than usual. As well as giving me new eyes, the South of France is also giving me a new nose.

Troglodyte to whom?

In English, we tend to associate the term troglodyte with a crude and uncivilised person, but in reality, the word also means someone who lived in caves in prehistoric times. Saint Roman is a troglodyte abbey in the latter sense. Carved out of the rock by hermits from the 5th century onwards, it remained active until 1538 thanks to Benedictine monks and is unique in Western Europe. From 1538 onwards it became a fortress, until around 1850 when the castle built on the upper terrace was destroyed.

My visit begins at the ‘sanctuary’, a natural cave used for prayer by the monks and then unfortunately exploited as a quarry in more recent centuries. I continue towards the choir, walking under a vaulted ceiling from the 13th century, where I find not only the sepulchre containing the relics of the saint who gives his name to this place but also the abbot’s seat (12th century) and the more modest prior’s seat.

Opposite, on the left of the irregularly shaped nave, is a series of tombs excavated both in the floor and in the walls. Above them, there is a block that resembles the alveoli of the lungs: in each small space, a lantern or an oil lamp was inserted. As I observe all this, I remind myself, dear readers, that I am here alone. I am here alone, immersed in an abbey carved into the rock more than 1500 years ago.

I continue my visit following the arrows and find myself on the terrace. From up there, at the top of the Aiguille hill which used to be an ocean, I can see the magnificent Rhone valley. All around me is the necropolis of the monastery, which covers almost the entire terrace. I think – macabrely, as usual – that it shouldn’t be so bad to end up resting up here. A little further on, beyond a grille, I catch a glimpse of an enormous cistern (containing up to 140,000 litres) designed to receive rainwater through a complex series of small canals also dug into the rock and covered with slabs.

I leave the terrace and descend from where I came up to reach a wide corridor that brings me in front of a gigantic empty space: these are what are simply but properly called the great common rooms. They are about 12 metres high, 17 metres long and 6.5 metres wide on average, and were once divided into three overlapping rooms: a stable, the dormitory, and the refectory. Near the large common rooms, there is a sign for the winepress, also carved entirely out of limestone. Before continuing, I stop and take note of what I am looking at. In the pages of the notebook from which these stories originate, dear readers, I wrote this sentence that afternoon: ‘When you write about this place, don’t be silly and remember to point out often that everything you see has been entirely carved by hand by man’.

Vitalis lived in this modest cell

The last part I visit is that of the monks’ cells and I don’t know what it is about this enormous hand-hewn mountain that makes me think of the rest of the world, but the primitive and essential aspect of these little rooms reminds me of the hermitages of Palestine, the monasteries of Armenia and Georgia, and of Cappadocia. There are no images, but the presence of these men who had detached themselves from earthly reality to (hopefully) arrive with great difficulty closer with the Otherworldly is very palpable.

As I lean out of one of the small windows through which only the sound of the wind and the song of the crickets enter, I see it. There is an inscription in Latin saying “Vitalis lived in this modest cell”.

The word demolishes hundreds of years between me and Vitalis, a monk, a hermit, a human being who had cut off all the material aspects of his existence. Throughout the abbey, there are no other inscriptions, not even the idiotic ones left by some tourists or asshole vandals. I photograph Vitalis’ letters. The written word, carved into the ochre-coloured limestone, has made Vitalis immortal.

The written word is a relationship not only with history but also with ourselves: the written language allows me to grasp the experience with awareness, to make it truly mine, to deepen it. For me, if I cannot write about something, that something often does not really exist. I think that when I manage (sometimes with great difficulty) to write about something, it is as if I manage to appropriate it more deeply. Plato would not be happy with this analysis because for him there was no relationship between reality and words.

For me, however, an impoverished relationship with words has always corresponded to an impoverished relationship with reality, or to put it more simply, as Moretti said, words are important. They make us unique in the universe, although the plant and animal worlds have very strong codes of expression. Written words allow us to fix life, to dominate it if this is then possible, to perform some sort of magic, to make us move or return to a place that is now far away.

Great that you include the map of where you travelled, as per our conversation

Super article as always. Love the inscription left by the monk, imagine , wow connect from the past in to the present.

As usual, thanks a million for your kind words. This place really holds a special place in my heart. I am glad you liked it too!